Related post on Christopher’s work: When Hall Signals Mislead

May 27

When Hall Signals Mislead

Hall measurements have long been a workhorse in condensed matter physics, offering a simple yet powerful way to probe electronic properties of materials. But as experiments increasingly venture into systems with mesoscopic spatial inhomogeneities, including, e.g., composition, magnetic domains, strain, and various moiré patterns, the interpretation of Hall measurements becomes less straightforward. A common assumption is that the measured Hall response from an inhomogeneous sample simply reflects an average of local Hall effects. But in reality, this is not always justified. Charge signals detected at the sample boundary are governed by global current paths and field distributions, which are shaped by the full spatial profile of the sample, not just its average properties.

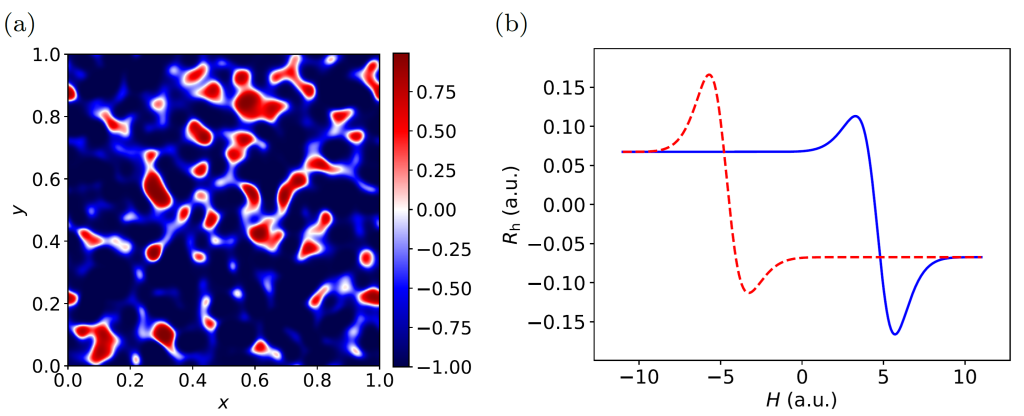

In a recent collaboration between physicists and mathematicians [1], we rigorously address this issue by deriving exact mathematical bounds on the global anomalous Hall conductivity (AHC) of inhomogeneous systems. Specifically, we prove that the measured Hall response must lie between the maximum and minimum values of the local anomalous Hall conductivity across the sample. This seemingly simple result provides a powerful diagnostic tool: Any apparent deviation of the measured signal outside this range can only arise from one of two possibilities—either the assumed local bounds are incorrect, or the measured quantity is not the true global anomalous Hall conductivity. Importantly, our framework allows for a clear classification of the often-debated Hall “hump” features (Figure below) observed during magnetic reversal in certain systems, distinguishing whether they originate from real topological effects (like skyrmions) or from magnetic and structral inhomogeneities.

We hope this work will serve as a robust anchor for interpreting future anomalous Hall experiments and perhaps inspire new ways of designing transport probes in magnetic materials.

Mar 25

Congratulations to Aidan for passing his PhD defense!

Aidan Winblad at his PhD defense on March 14, 2025.

Related post on Aidan’s work: Triangulating Majorana fermions

Mar 12

Physicists Uncover “Hall Mass” Driving Spin Currents Sideways in Advanced Magnets

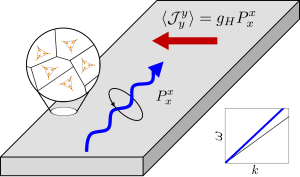

A team of researchers led by Colorado State University graduate student Luke Wernert and Associate Professor Hua Chen has discovered a new kind of “Hall effect” that could enable more energy-efficient electronic devices. Their findings, published in Physical Review Letters in collaboration with graduate student Bastián Pradenas and Professor Oleg Tchernyshyov at Johns Hopkins University, reveal a previously unknown “Hall mass” in complex magnets called noncollinear antiferromagnets.

The Hall effect—first discovered by Edwin Hall at Johns Hopkins in 1879—usually refers to electric current flowing sideways when exposed to an external magnetic field, creating a measurable voltage. This sideways flow underpins everything from vehicle speed sensors to phone motion detectors. But in the CSU team’s work, electrons’ spin (a tiny, intrinsic form of angular momentum) takes center stage instead of electric charge. Noncollinear antiferromagnets, unlike more familiar magnets where spins line up parallel or antiparallel, have spins oriented in different directions but still sum to zero net magnetization. This unique spin texture enables a fresh take on the Hall effect, where spin currents can flow at right angles rather than just electric charges.

“Imagine pushing a spin current in one direction and getting a second spin current going sideways,” Wernert explains. “That’s the hallmark of a Hall effect.” The reason this new effect—governed by the “Hall mass”—appears only in noncollinear antiferromagnets is because they have three degrees of freedom describing spin orientations. This extra complexity leads to three branches of spin waves (collective vibrations of the spins), two of which naturally flow sideways in response to a driving force. Experimentally, researchers can measure this Hall mass either by injecting spin waves from a conventional ferromagnet into a noncollinear antiferromagnet and detecting spin accumulation along the edges, or by using scattering techniques (like neutron or x-ray) to track the low-energy spin-wave spectrum.

Because spin currents produce far less heat than electrical currents, harnessing them could revolutionize modern electronics. This prospect underlies the rapidly growing field of “spintronics,” which strives to build devices—such as magnetic-based storage (Magnetoresistive Random-Access Memory, MRAM)—that are more energy efficient and resistant to data corruption by external magnetic fields. In conventional magnetic materials, a stray magnetic field can sometimes wipe out stored information; by contrast, noncollinear antiferromagnets are much less susceptible to such interference, making them potentially safer for data storage and handling. Altogether, the discovery of this new Hall effect and its associated Hall mass opens an exciting direction in condensed matter physics and could guide the development of next-generation technology powered by spin.

Luke Wernert, Bastián Pradenas, Oleg Tchernyshyov, and Hua Chen, “Hall mass and transverse Noether spin currents in noncollinear antiferromagnets”, arXiv:2404.12898, Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 016706 (2025).

Jun 19

Triangulating Majorana fermions

Topological quantum computation (TQC) based on Majorana zero modes (MZM) has been actively pursued in the past decade. Aside from well-recognized challenges in unambiguously identifying MZM in existing effective one-dimensional p-wave superconductors, the next step of demonstrating braiding of MZM is even more formidable. The most prevalent proposal on realizing braiding operation is based on networks of effective p-wave superconductor wires subject to many tiny electric gates that are distributed along the wires and can be sequentially turned on or off, so that the MZM can be adiabatically moved across different parts of the network. It is then a natural question to ask if there exists an alternative, possibly more practical architecture for braiding MZM, that may even be more friendly to near-term MZM systems.

Motivated by this question, as well as the recent experimental breakthrough on demonstrating MZM in a minimal Kitaev chain consisting of only two quantum dots [Dvir et al., Nature 614, 445 (2023)], we propose in [1] a couple of new structures for braiding MZM based on triangular superconducting islands that can either be constructed in a bottom-up manner as a minimal extension of the two-site Kitaev chain, or appear naturally in epitaxial growth of ultrathin films. For the former case, we have shown that a minimal 3-site “Kitaev triangle” can host MZM at different pairs of vertices that can be controlled by a non-uniform vector potential. We have demonstrated braiding two MZM in this minimal model by explicitly calculating the many-body Berry phase. For the latter case, we have extended the 3-site Kitaev triangle to a finite-size triangular island with a hollow interior. We have shown that using a uniform vector potential, one can induce a pair of MZM at different pairs of vertices of the triangle. Moreover, rotating the uniform vector potential can change the positions of the MZM without closing the bulk band gap, i.e., adiabatically. Finally we have given a scalable design, backed by numerical calculations, for braiding two out of four MZM that corresponds to nontrivial logical gate operations, in a network of corner-sharing hollow triangles.

Our work provides a novel platform in parallel with the coupled-wire network design for braiding MZM, and is practical especially considering near-term MZM devices. The Kitaev triangle offers an alternative strategy towards MZM-based TQC that is not based on bulk-boundary correspondence, which may be easier to realize in near-term quantum-dot=based devices than coupled wires. On the other hand, our proposal of a uniform vector potential coupled to hollow triangles explores the utility of geometry rather than the individual control of superconducting nanowires. It highlights that triangles, as a geometry, are unique compared to other quasi-2D structures such as wires, squares, or circles, since they naturally break 2D inversion symmetry and do not present a straightforward strategy for morphing into either 1D or 2D structures with periodic boundary conditions.

May 03

Tunneling current-controlled spin states in few-layer van der Waals magnets

The phenomenon of spin-transfer torque in bilayer metallic ferromagnets is well understood in terms of Landau-Lifshitz equation modified by magnetic torques carried by electric currents. However, when each ferromagnet layer is replaced by a single atomic layer of vdW magnetic insulators and electric transport through the bilayer is highly coherent, is the above picture still applicable? In a recent collaborative work [1], we argued that switching between layer-resolved collinear antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic states in bilayer insulating CrI3 is achieved by tunneling-current-induced spin accumulation of opposite signs at metallic electrodes in contact with the respective CrI3 monolayers, which from a symmetry point of view is a general mechanism for switching between uniform and nonuniform magnetic states. A pedagogical news article summarizing the main findings of the work can be found here.

[1] ZhuangEn Fu, Piumi I. Samarawickrama, John Ackerman, Yanglin Zhu, Zhiqiang Mao, Kenji Watanabe, Takashi Taniguchi, Wenyong Wang, Yuri Dahnovsky, Mingzhong Wu, TeYu Chien, Jinke Tang, Allan H. MacDonald, Hua Chen* & Jifa Tian*, “Tunneling current-controlled spin states in few-layer van der Waals magnets”, Nature Communications 15, 3630 (2024).

Feb 07

Quantum interference in density wave systems

When hearing “pi-phase” and “quantum oscillations”, would you immediately jump to Berry phase? In a recent collaborative work, we have shown that a new kind of “pi-phase shift”, i.e., that between quantum oscillations in longitudinal resistivities along orthogonal directions, in the prototypical spin density wave material Cr, is caused by quantum interference effects between coupled semiclassical orbits. For an in-depth introduction, see this note which was a presentation given at the “Magneticians’ meeting” at Johns Hopkins University in 2023.

Jan 30

Unexpected symmetry in kagome spin ice revealed by electrical transport

Since the original proposal by Anderson on spin liquid being a possible mechanism for high-Tc superconductivity, electrical transport in frustrated quantum spin systems has always been one of the most enticing topics in condensed matter physics. However, a majority of quantum spin ice and spin liquid candidates are good insulators, making it challenging for standard electrical transport techniques. In contrast, in the few cases of metallic frustrated spin systems, transport experiments usually lead to surprising discoveries.

In this collaborative work, through electrical transport experiments on a recently identified metallic kagome spin ice compound HoAgGe, we made another surprising discovery: There exists a time-reversal-like degeneracy for certain noncollinear ice-rule states on field-induced magnetic plateaus, which have the same energy and magnetization, but different sizes of the anomalous Hall effect (AHE). Since the AHE transforms as a pseudovector with fixed length under all magnetic group operations, the symmetry operation underlying such a degeneracy is beyond the standard paradigm of magnetic space group for classifying magnetic structures.

Through comprehensive neutron refinement and numerical search in the degenerate ice-rule manifold, we are able to nail down the spin structures of the degenerate states and to come up with a microscopic model for calculating their transport properties. Again surprisingly, we find that the degenerate spin structures have exactly the same band structure, but different Berry curvatures in momentum space, and hence different sizes of the anomalous Hall effect. Although the Berry curvature is more related to the geometric properties of the Bloch wavefunctions than to the eigenenergies, it is hard to imagine without seeing that real physical systems with identical band structures can have different Berry curvatures.

Our systematic experimental and theoretical efforts elucidated the rather subtle symmetry operation that connects the degenerate states, which critically relies on a reversal of lattice distortion in the structure of HoAgGe. Since the Berry connection inherently depends on the atomic location in a unit cell, while the latter is largely invisible to the momentum space Hamiltonian, the distortion reversal in such a quasi-symmetry operation eventually changes the size of the AHE but not the band structure.

Our work is built upon the active research in the topical areas of quantum spin ice systems and anomalous transport in noncollinear antiferromagnets, but advances these fields by cross-disciplinary findings that crucially require ingredients from both: The massive ground state degeneracy of frustrated spin systems provides a reservoir for novel noncollinear spin configurations that host characteristic anomalous transport properties. Our work also points to the special role of lattice distortion and distortion reversal in quantum spin systems. In particular, our theoretical analysis indicates that similar phenomena should generally occur in quantum spin systems with nontrivial lattice distortion and relatively weak spin-orbit coupling.

Sep 07

Transporting the shape of spin

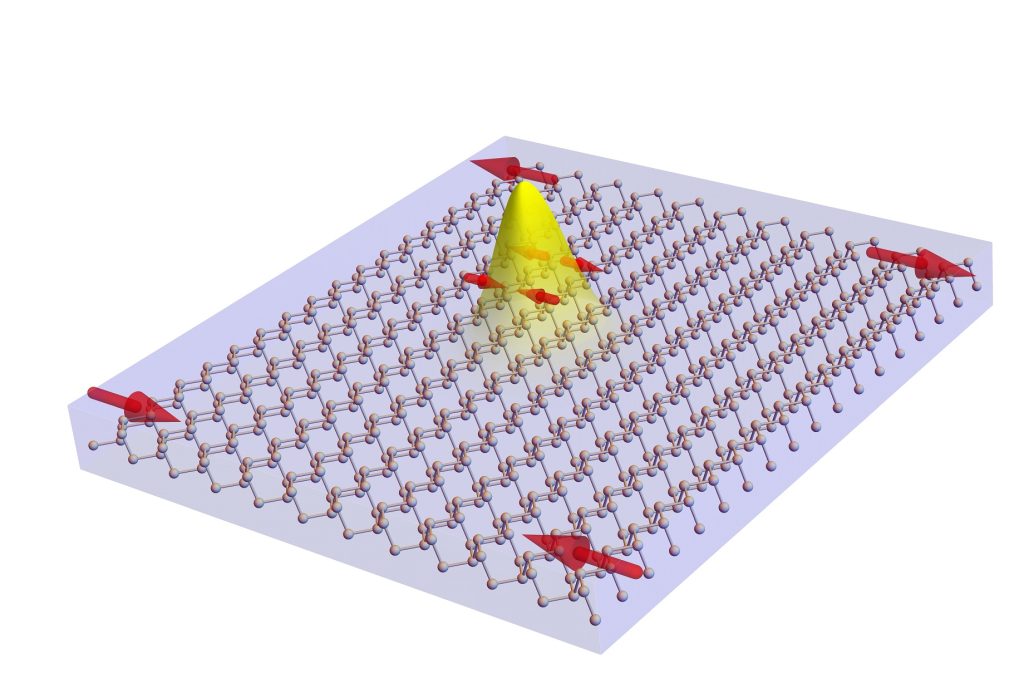

Spintronics exploits the idea of using electron spin instead of charge to encode and process information. But can electrons carry more than just spin across diverse materials? Our work answers with a resounding yes, unveiling the transport of spin “shape” in solids. The word “shape” means how spin is distributed spatially about the center of mass of a single electron wave packet. In practice it can be described by the multipole moments of spin distributions. We have isolated the part of such multipole moments that does not depend on how the wave packets are constructed, thus having an absolute meaning. Similar to spin, the well-defined spin or magnetic multipole moments can then be transported by electrons driven by external fields. As one example, we showed that an electric current flowing through phosphorene subjected to a perpendicular electric field can generate magnetic octupole moments. Such octupole moments are manifested by accumulation of spins with alternating signs at square sample corners, as illustrated in the figure below. Our work propels the emergence of “multipoletronics,” a promising new phase beyond spintronics.

Jul 22

An alternative to magnetization

In the ordinary Hall effect, it is the magnetic field that tells which way the electric currents driven by a voltage bias should be deflected, simply through the Lorentz force. In a ferromagnetic conductor, it is the direction of the magnetization that determines that of the transverse anomalous Hall current flow, despite the more complicated microscopic mechanisms. However, for antiferromagnets when the magnetization vanishes but the anomalous Hall effect does not, how can the electrons know which way they should be deflected? In this work we answered this question by introducing a new quantity named as electronic chiralization (EC), that is determined by the spatial gradients of the microscopic magnetization rather than its mean. EC transforms in exactly the same way as the anomalous Hall vector under all space group operations, including continuous translation, and is free from the difficulties of defining multipole moments of infinite systems. Moreover, EC provides intuitive guidance for the search of new unconventional magnetic systems hosting the AHE as it suggests what types of spin and charge textures are necessary for the AHE. To demonstrate this we provided two novel, experimentally relevant examples: charge-ordered kagome spin ice, and 2D Dirac electrons skew-scattered by a magnetic charge texture. The former may solve the puzzle of the experimentally observed AHE in certain frustrated spin systems that lack long-range magnetic dipole order, while the latter demonstrates another paradigm of noncollinear magnetic textures, magnetic charge or monopole, that can give rise to the AHE, in contrast to the well-known scalar spin chirality and skyrmions.

Electronic chiralization as an indicator of the anomalous Hall effect in unconventional magnetic systems

Hua Chen, Phys. Rev. B 106, 024421 (2022).

- 1

- 2