A team of researchers led by Colorado State University graduate student Luke Wernert and Associate Professor Hua Chen has discovered a new kind of “Hall effect” that could enable more energy-efficient electronic devices. Their findings, published in Physical Review Letters in collaboration with graduate student Bastián Pradenas and Professor Oleg Tchernyshyov at Johns Hopkins University, reveal a previously unknown “Hall mass” in complex magnets called noncollinear antiferromagnets.

The Hall effect—first discovered by Edwin Hall at Johns Hopkins in 1879—usually refers to electric current flowing sideways when exposed to an external magnetic field, creating a measurable voltage. This sideways flow underpins everything from vehicle speed sensors to phone motion detectors. But in the CSU team’s work, electrons’ spin (a tiny, intrinsic form of angular momentum) takes center stage instead of electric charge. Noncollinear antiferromagnets, unlike more familiar magnets where spins line up parallel or antiparallel, have spins oriented in different directions but still sum to zero net magnetization. This unique spin texture enables a fresh take on the Hall effect, where spin currents can flow at right angles rather than just electric charges.

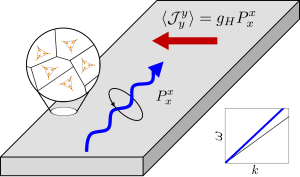

“Imagine pushing a spin current in one direction and getting a second spin current going sideways,” Wernert explains. “That’s the hallmark of a Hall effect.” The reason this new effect—governed by the “Hall mass”—appears only in noncollinear antiferromagnets is because they have three degrees of freedom describing spin orientations. This extra complexity leads to three branches of spin waves (collective vibrations of the spins), two of which naturally flow sideways in response to a driving force. Experimentally, researchers can measure this Hall mass either by injecting spin waves from a conventional ferromagnet into a noncollinear antiferromagnet and detecting spin accumulation along the edges, or by using scattering techniques (like neutron or x-ray) to track the low-energy spin-wave spectrum.

Because spin currents produce far less heat than electrical currents, harnessing them could revolutionize modern electronics. This prospect underlies the rapidly growing field of “spintronics,” which strives to build devices—such as magnetic-based storage (Magnetoresistive Random-Access Memory, MRAM)—that are more energy efficient and resistant to data corruption by external magnetic fields. In conventional magnetic materials, a stray magnetic field can sometimes wipe out stored information; by contrast, noncollinear antiferromagnets are much less susceptible to such interference, making them potentially safer for data storage and handling. Altogether, the discovery of this new Hall effect and its associated Hall mass opens an exciting direction in condensed matter physics and could guide the development of next-generation technology powered by spin.

Luke Wernert, Bastián Pradenas, Oleg Tchernyshyov, and Hua Chen, “Hall mass and transverse Noether spin currents in noncollinear antiferromagnets”, arXiv:2404.12898, Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 016706 (2025).

Recent Comments